5 Things to Look For in Probate Records to Help Trace Your Ancestors

*This post may have affiliate links, which means I may receive commissions if you choose to purchase through links I provide (at no extra cost to you). All opinions remain my own.

Have you tried looking for the wills and estate records of your ancestors?

Estate records should be one of the top records you look for because they can be jam-packed with information. Of course, they vary by what you can find in them, but I’ve always learned something new after finding one of these records.

What are estate records?

Estate records are formally called probate records, which is a court process to oversee the distribution of an estate of someone who has died.

Someone could die testate or intestate. Testate means they’ve left a will. Intestate means they didn’t leave a will. Inheritance laws differ by state, but generally, the spouse and any children will inherit the estate if someone dies intestate.

For African American genealogy research, estate records can be even more valuable. Before emancipation, if a white man wanted his mixed-race child freed after his death, his family could challenge it in court, leaving a trail of court records.

Probate records existed before death and other vital records became required and commonplace. They might be the only record you can find documenting someone’s death and family relationships.

Estate records weren’t only for rich people, either. I made this assumption with my family for a long time because many were less well-off, so I put off looking for any. But, about 25% of heads of households in the US before 1900 had a probated estate. Estates were more common in farming areas because of the higher chance of owning land.

If you’ve been here before, you might have heard me say this, but I suggest you transcribe everything on the document, even the typed sections.

Transcribing makes you read through everything closely. It also makes it easier to go back and reference later. Don’t keep rereading the same terrible handwriting if you don’t have to!

What you can find in probate records

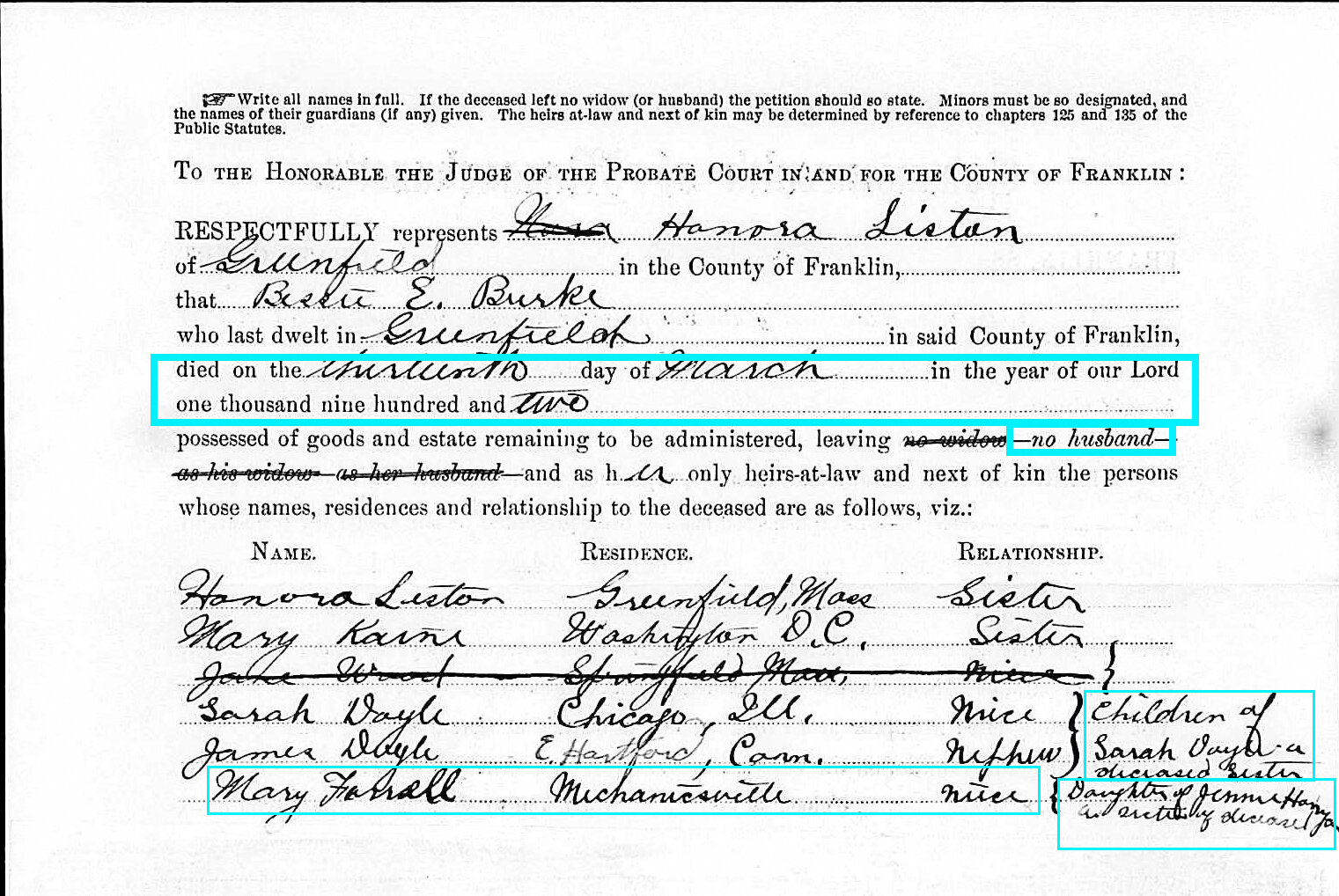

1) When and where the person died. It may be a year, the month and year, or a complete date. But even a year is a good starting point for further research.

2) Their children’s names and locations. For daughters, you can find their married names, and sometimes their husbands’ names.

Not all kids may be listed in an estate record, though. Sometimes money or land had already been given to a child, so they wouldn’t be named in the will. Daughters may have received their share of the estate when they got married.

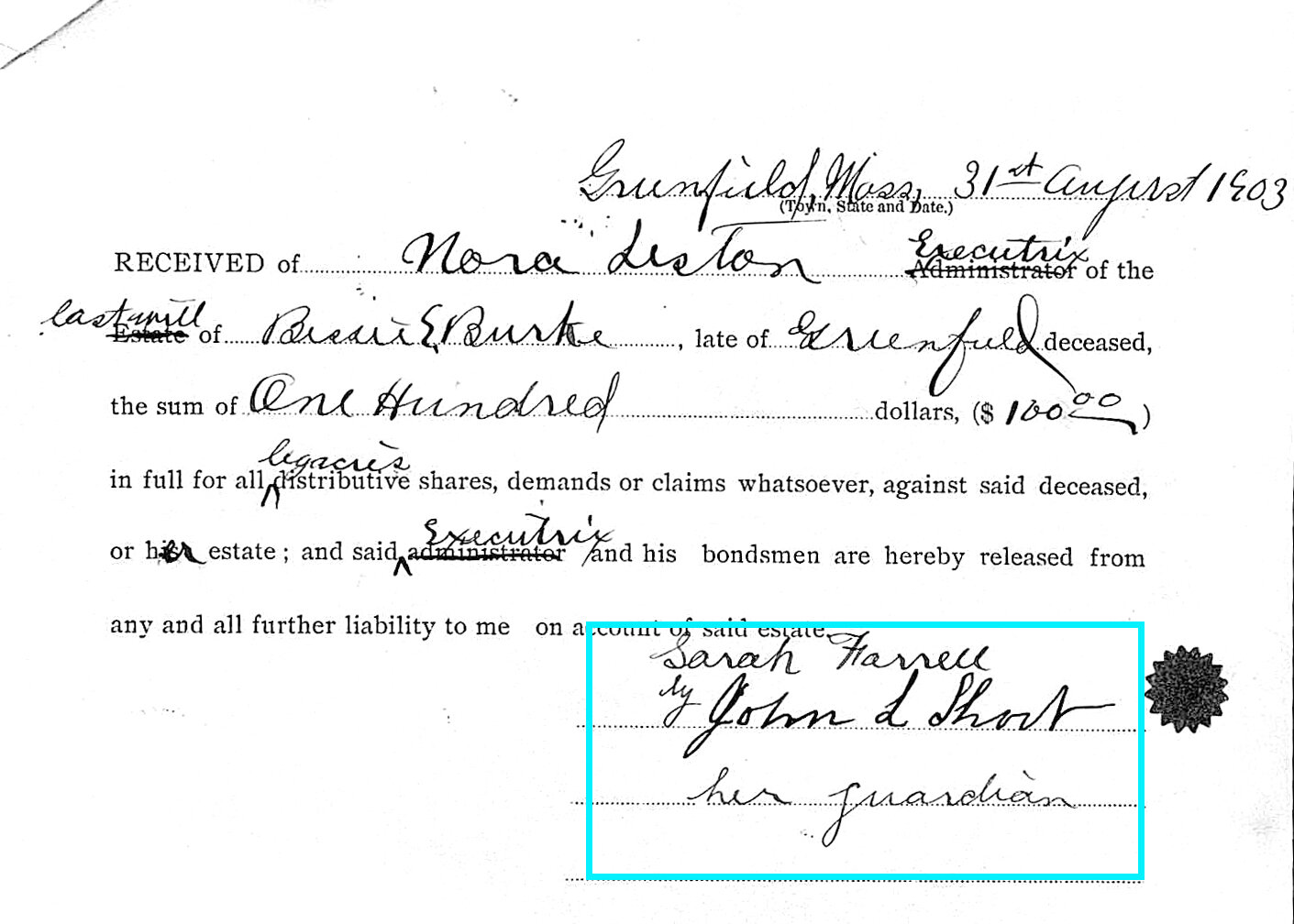

When someone died leaving minor children (under 21) behind, they received guardians, which made even more paperwork. Kids under 14 were appointed guardians by the court. Children over 14 could choose their own.

In the will of my 3rd great aunt, the guardian for her niece, Sarah Farrell, was named as John L. Short. This is a fact I may not have found anywhere else and gives me another person to research to find records for Sarah.

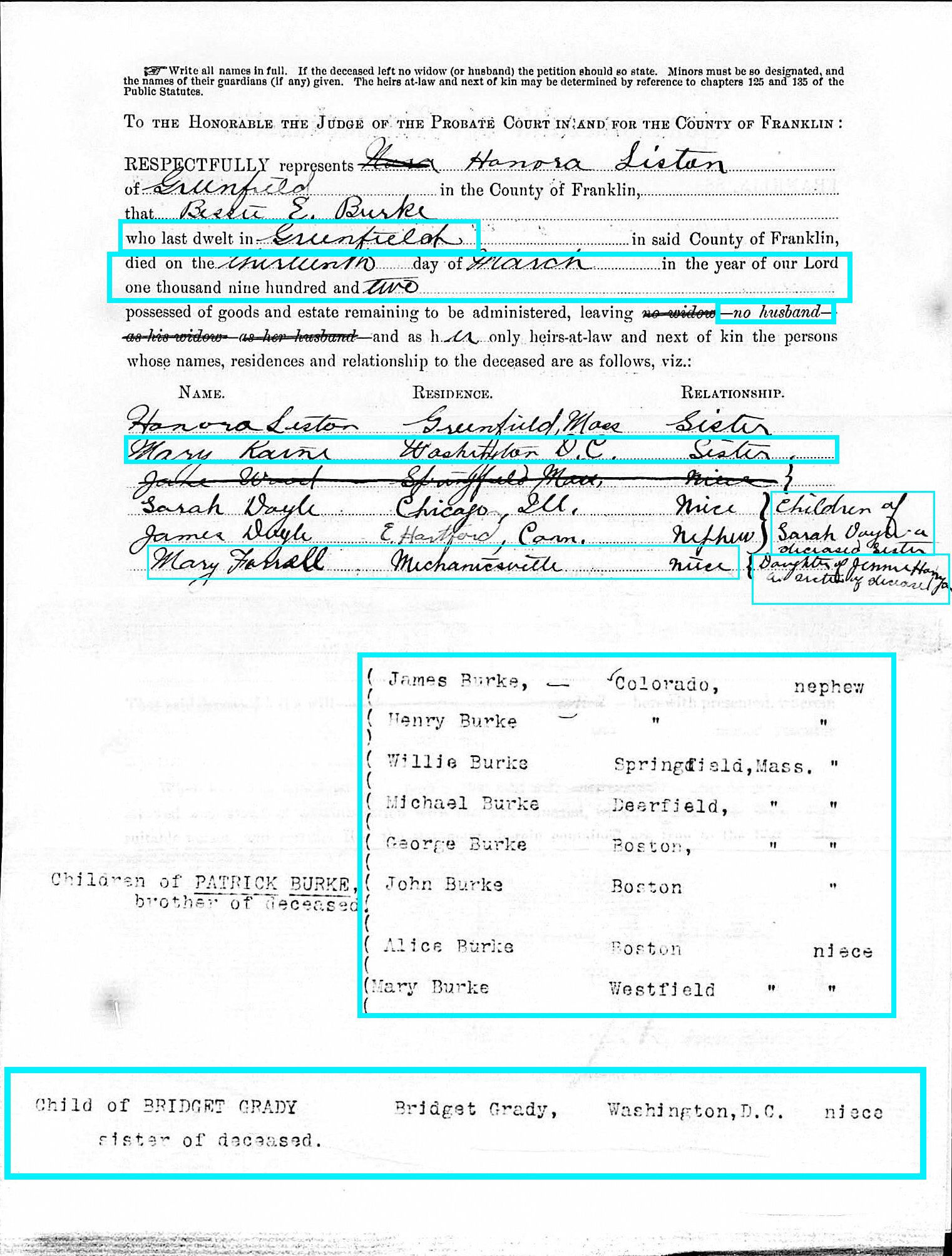

3) Siblings and other family members and where they lived. With Bessie Burke, my 3rd great aunt’s probate record, I found 3 new sisters I didn’t know existed. I suspected my 3rd great grandfather, Patrick Burke, had more siblings, but this probate was the first I learned of their names.

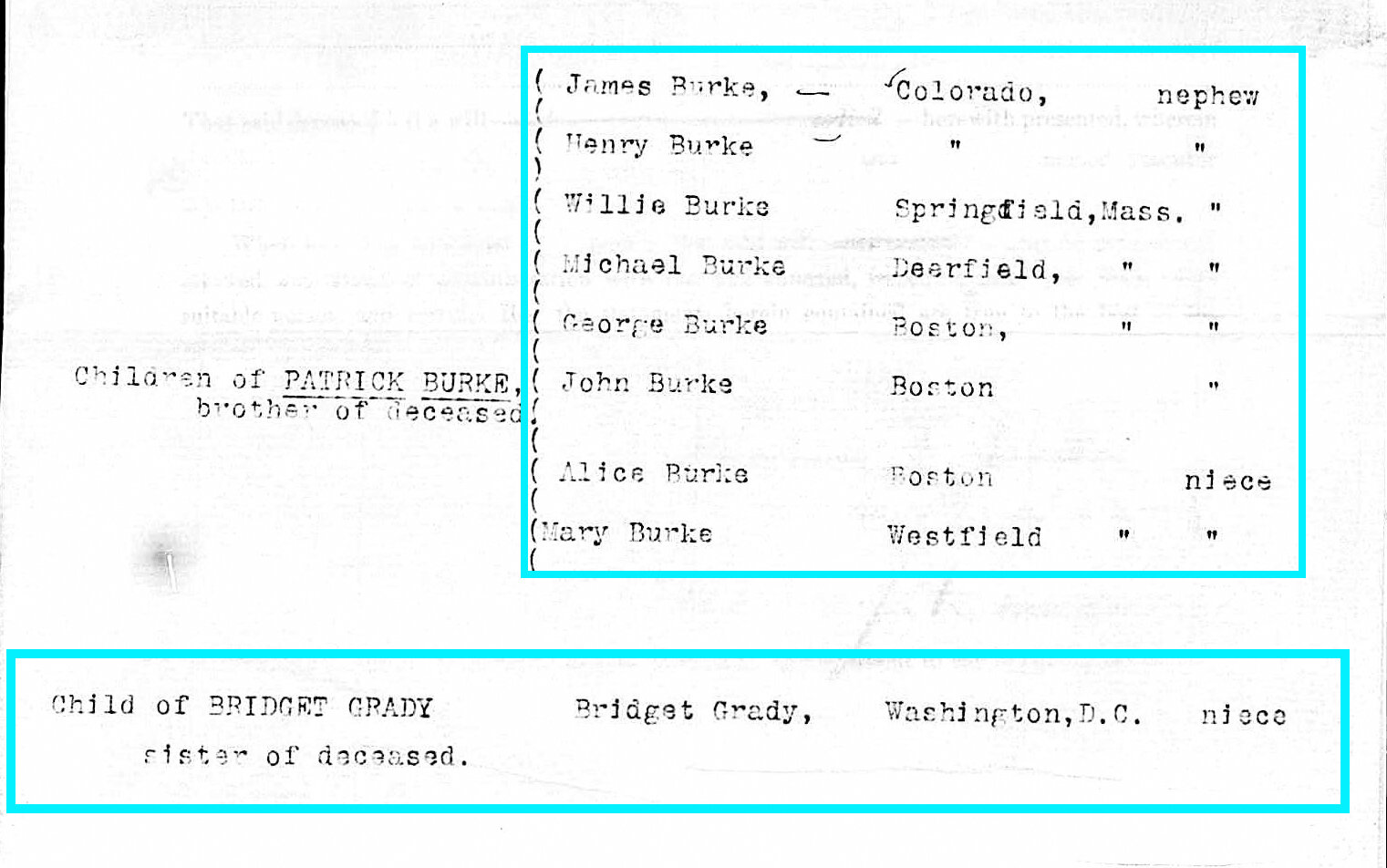

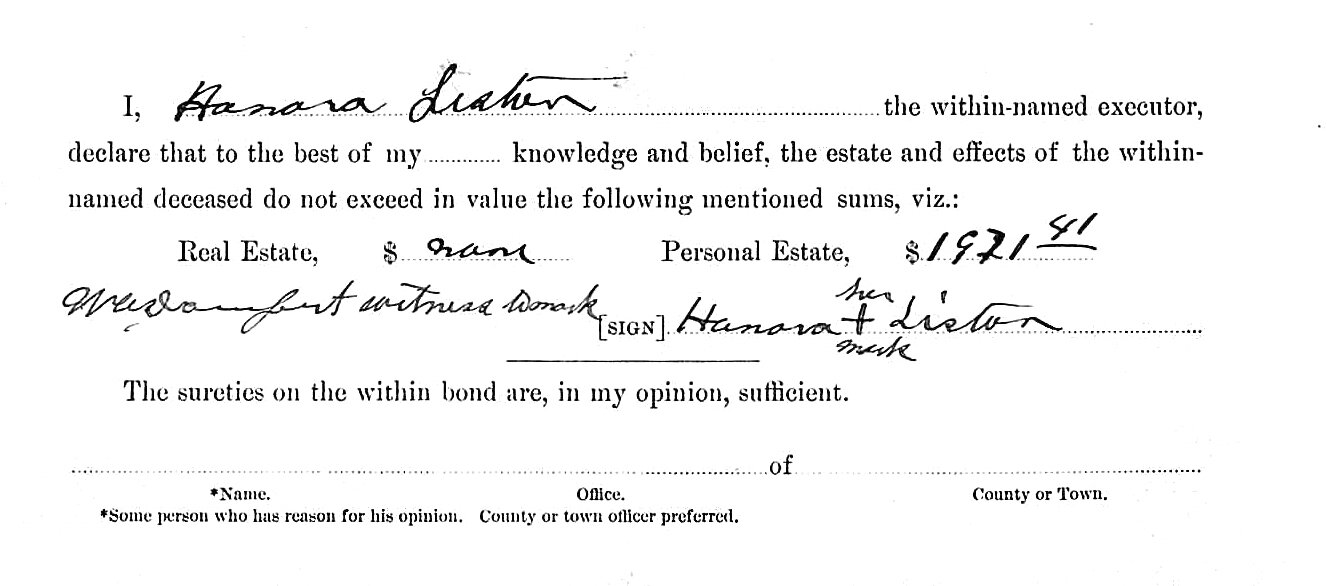

As you can see on the first main page of the estate record, there’s a lot of information to extract!

[Source: Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9069/images/007704707_00803?pId=6724384 : accessed 10 November 2020) > Massachusetts, Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 > Franklin County > Probate Files, 13475-13533 > Case 13518, Bessie E. Burke, 18 March 1902.]

Let’s break it down. It gives her date of death as 13 March 1902 and her last residence as Greenfield [Massachusetts]. She had no husband.

In the first section, it names siblings Hanora [aka Honora or Nora] Liston of Greenfield, Massachusetts, Mary Kane of Washington D.C., Sarah Doyle, deceased, Jennie Hanyan [?], deceased. I had never heard of Mary Kane or Jennie Hanyan before finding this.

It also names Jennie’s daughter, Mary Farrell of Mechanicsville [New York]. For some reason, Jane Wood of Springfield, Massachusetts was crossed out.

The second section lists all the children of my 3x great grandfather, Patrick, and where they were living. This all gives more data points for my timeline for the family. With a name like Burke, it can be hard to track their movements, so these details help pin them down.

Then, Bridget Grady of Washington DC, the child of deceased sister Bridget Grady, is named. Bridget Grady is another sister of Patrick’s that I didn’t know existed.

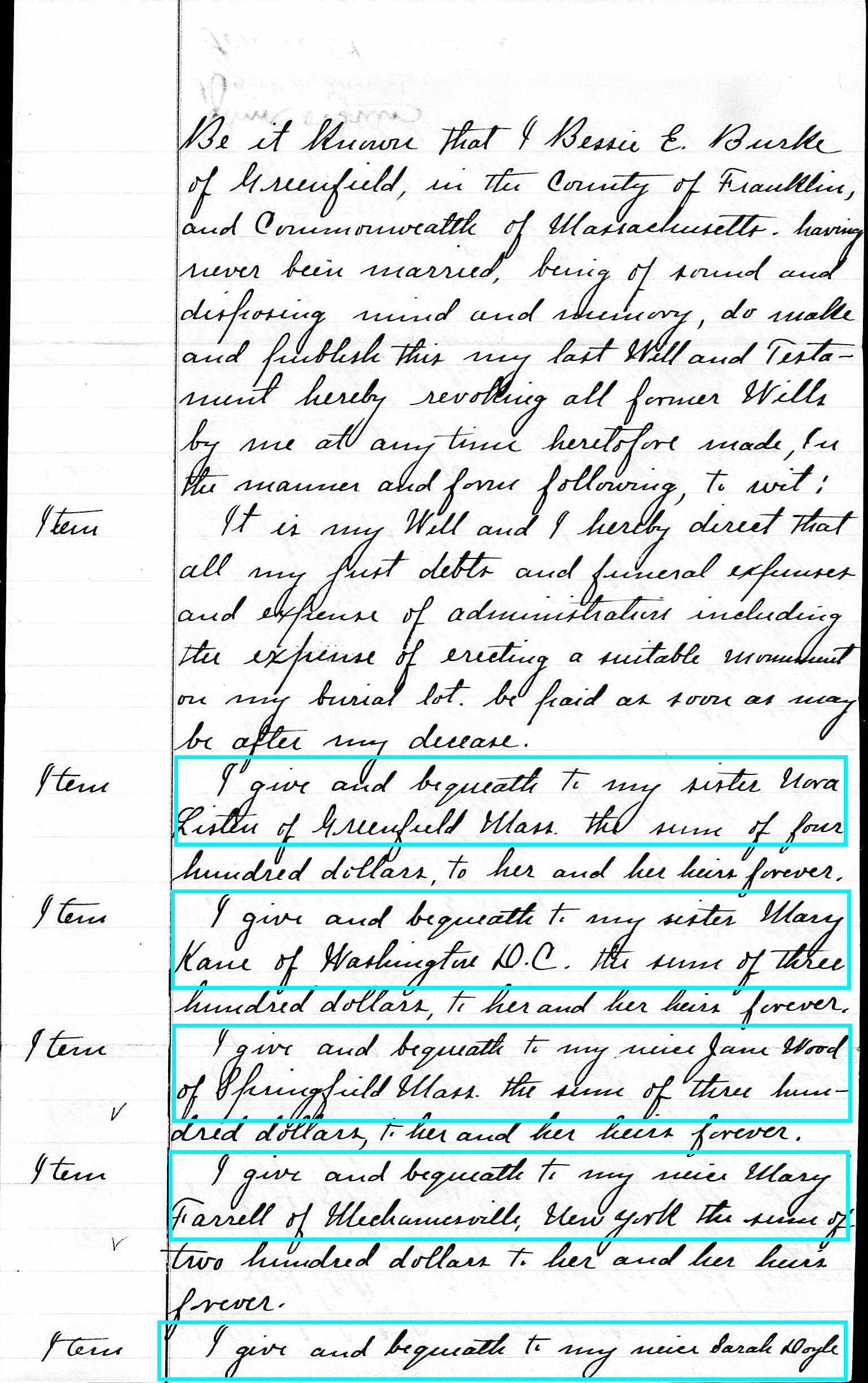

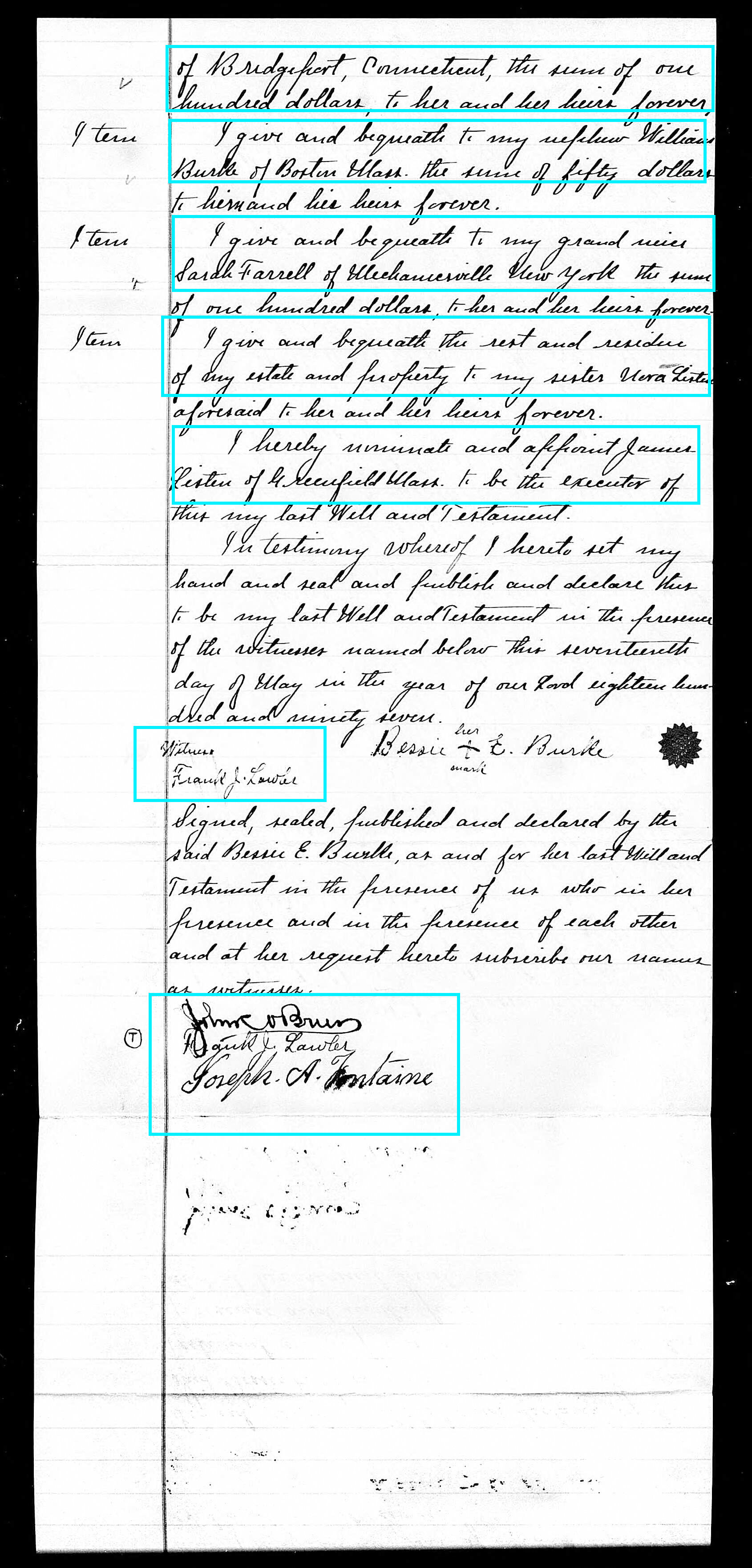

Her will goes on to show how much she left to several family members. Not all were bequeathed something. Only one of Patrick’s children received anything.

The will appointed her brother-in-law, James Liston of Greenfield, to be the executor.

Three witnesses are named: Frank J. Lawler, what looks like maybe John C. Brown, and Joseph A. Fontaine.

It’s important to research any witnesses on documents because you never know who they might be.

I know from other research that Frank J. Lawler was a lawyer in town, who also happens to be my 1st cousin 5x removed on another branch. I need to research who John and Joseph were.

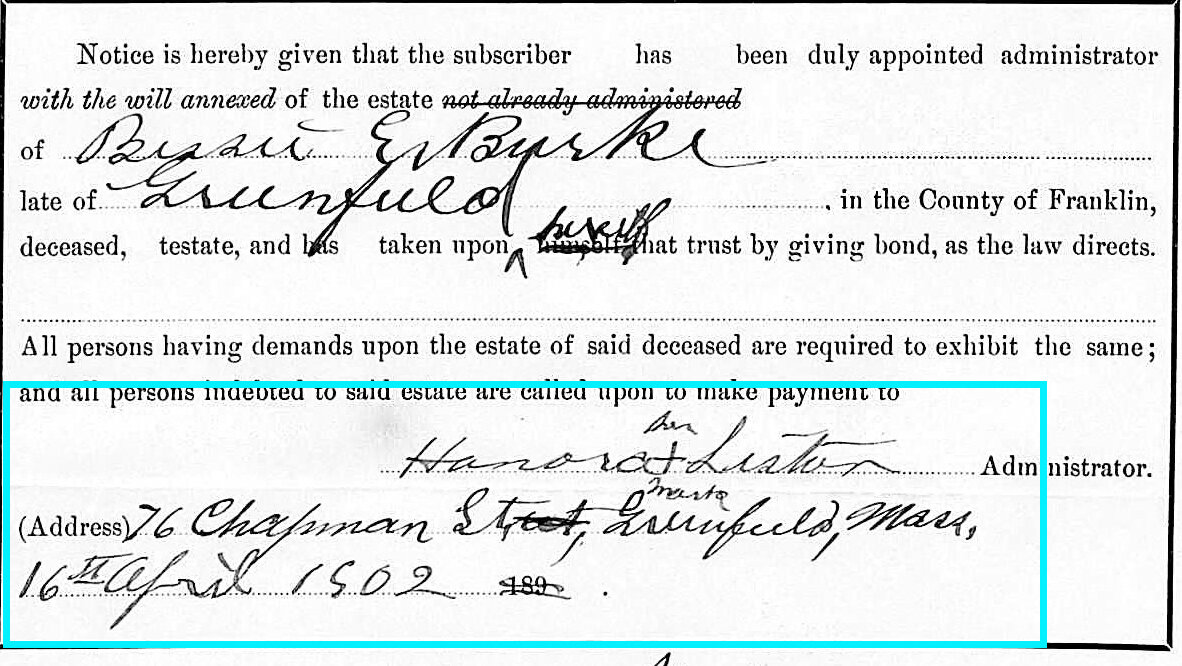

Wills generally give only the towns people lived in, but sometimes exact addresses were included. In Bessie’s probate record, her sister Honora Liston’s address at 76 Chapman Street in Greenfield was noted.

4) What they owned. The inventory may tell you if they were wealthy. It could give you clues about what kind of work they did, like if farm tools were mentioned. It will tell you if they owned land and where their property was. For African American research, these documents are essential because they can tell you about slaves and their possible relationships.

Bessie didn’t own any land, but she did have $1971 in her personal estate, about $59,000 today. Not too bad for someone who was a servant.

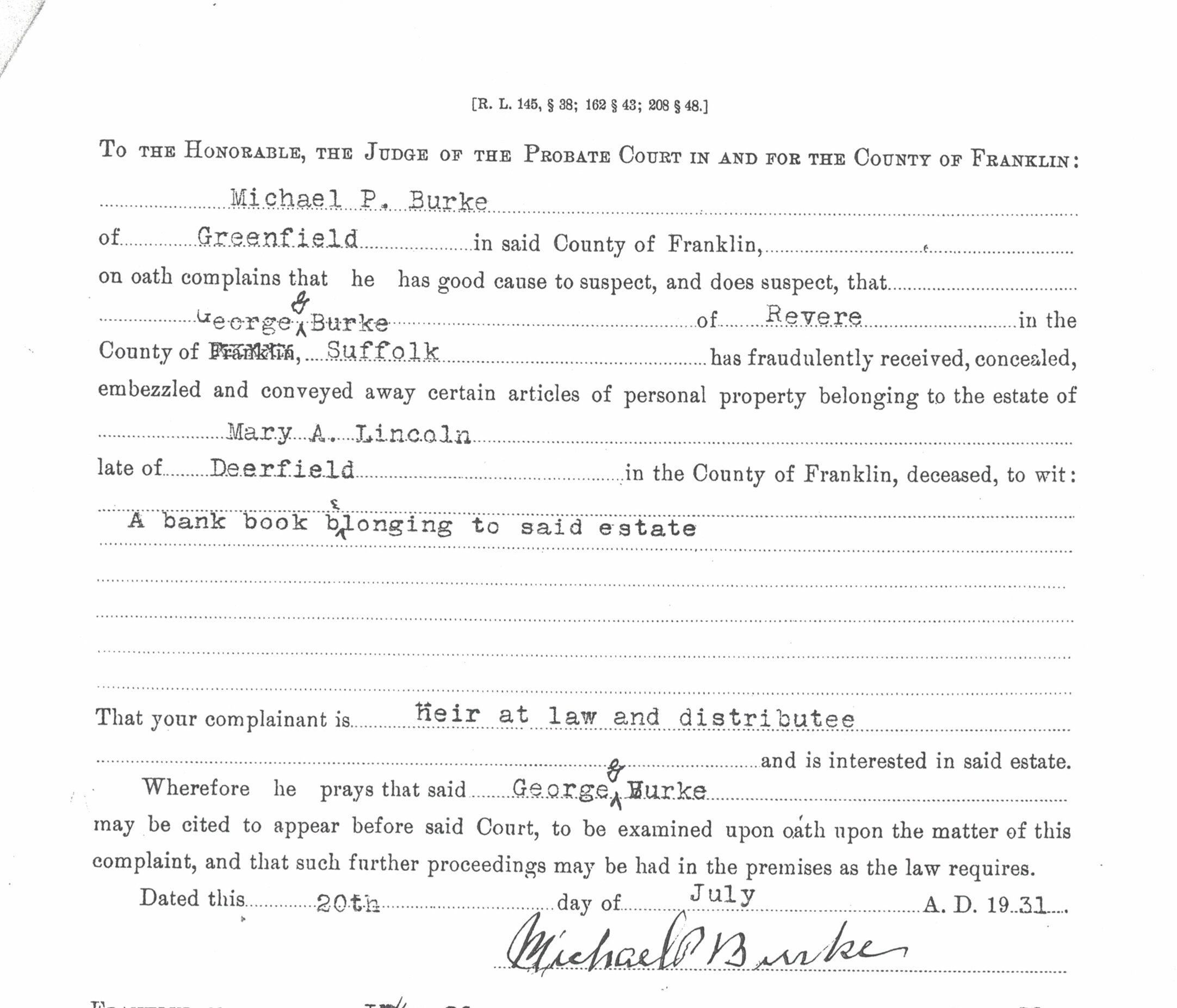

5) Family drama. Sometimes families got into arguments over estates. These claims generated more records, yay for us!

[Source: my personal collection]

My 2x great grandfather, Michael Burke, accused his brother, George, of embezzling money from their sister Mary’s estate. George had been appointed the estate administrator. There were a couple of pages in the file about it, but Michael died shortly after so I’m not sure if anything was resolved.

It’s still an interesting thing to learn even if I don’t know how it turned out.

What to do with what the details you find

After you’ve extracted all the info from the records, look at what you’ve found and figure out what you need to research.

For the deceased, look for any other death-related records you don’t already have, like funeral home records and obituaries.

For every relative mentioned, start with looking for their vital records and in censuses. For married daughters, look for their marriages.

For minor children under guardianships, research the guardians. See if more probate records exist for the guardianship, especially around the time the child aged out at 21.

If a relative is named as living in a town you didn’t know they lived in, research city directories and censuses to pin down their address. Try town histories to see if they appear in them. Contact the local historical society to see if they have any documents or photos for them.

For any unknown person that shows up, research them to see if you can figure out what was their relationship to the dead person was.

I only found Bessie’s estate record a few weeks ago, but it’s given me so many new paths to look into!

How to find probate court records

Probate records are available in a few different places.

Some are online. Ancestry.com has some for a good number of states, as well as a few other countries. FamilySearch also has probate records, although some are only viewable at Family History Centers.

County courthouses. Many local courthouses still have probate records. Contact them to see how to access them. Sometimes they will look them up for you. If so, you pay a fee to get a copy.

Family History Centers. As I said above, some of FamilySearch’s probate collections are only available through an FHC.

Historical societies. Historical societies may have copies of estate records. I was able to get copies of two ancestors’ estates through one, years before it was available online.

State archives. Sometimes county courthouses will have transferred the older records to the state archives. For example, the New York State Archives has wills and probate records from the 1600-1700s.