How Using Mortality Schedules Can Improve Your African American Genealogy Research

*This post may have affiliate links, which means I may receive commissions if you choose to purchase through links I provide (at no extra cost to you). All opinions remain my own.

People researching African American family trees have to face unique obstacles in their work, but there are resources out there to help.

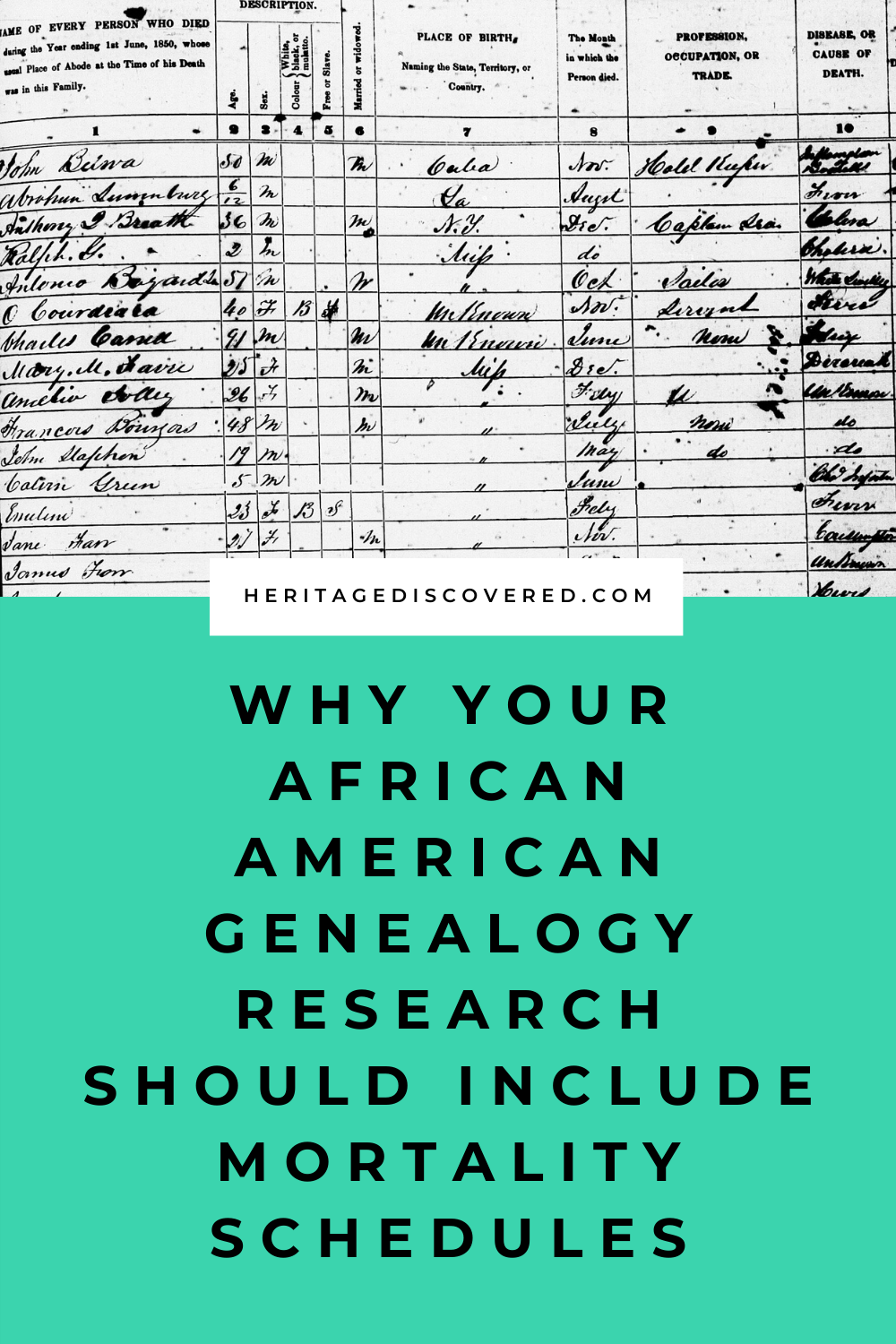

The 1850 and 1860 mortality schedules are one of the key sources for pre-Civil War research for African Americans.

Why? Because enslaved people who died within the year before were often named in these documents.

As you probably know, since slaves were seen as property and not people, there are few records documenting their names and lives.

Also, vital record-keeping didn’t exist as we know it today. These schedules could be the only place their deaths were recorded.

Related post: 10 Black Genealogy Resources You Need to Know

1st column: name. 2nd column: age. 3rd column: gender. 4th column: color. 5th column: free or slave. 6th column: where born.

What are mortality schedules and why are they helpful?

Mortality schedules are one of the non-population schedules taken along with the census. They list the people who died in the 12 months before that respective census year.

These schedules were collected from 1850 to 1880 (and 1885 in a few states).

In 1850 and 1860, the schedules asked if the deceased person was free or enslaved, along with other details, making them valuable for African American genealogy.

Even though they only captured deaths for the year before, they can identify family members and owners' names, leading to other records with more information.

Related post: Everything You Need to Know About Using Home Sources

What you can learn from mortality schedules

What can you find on a mortality schedule?

Both the 1850 and 1860 schedules asked for:

name

age

sex

color (White, Black, or Mulatto)

whether free or a slave

married or widowed

place of birth

month died

profession or trade

disease

number of days ill

For many slaves, only their first name was used. In some cases, no name was mentioned at all except for the owner, along with the age and gender of the enslaved person.

But some were recorded with a last name, and occasionally also had their owner’s name listed.

In these cases, they and the owner can be traced in the slave schedules, probate records, land deeds, and other sources that might tell more of the enslaved person’s story.

Try browsing the schedule for the county your ancestor was from. Many are only a few pages long and easy to page through.

Related post: How to Find and Use the Hidden Clues in Obituaries

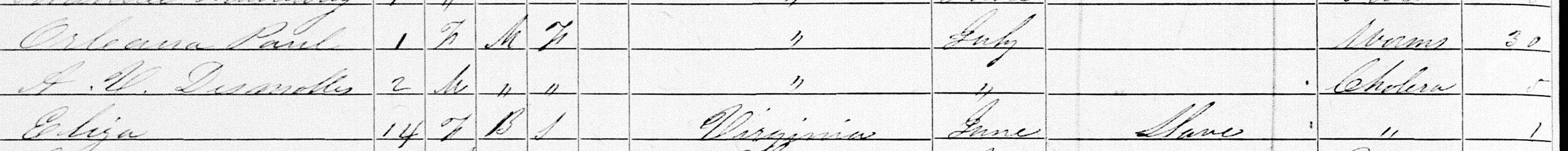

Orleana Paul and A. V. Desmolles were free Mulatto children in Louisiana.

Where to find the schedules

Mortality schedules aren’t available online for every state.

These records can be accessed in a few different places.

1) FamilySearch has the 1850 schedule for you to search online. But not all places have images. Some locations have been indexed, but the images aren’t viewable outside of a Family History Center.

2) Ancestry has the mortality schedules for 1850-1885 for most places. You can look at the source data to see if they have the state and year you want.

3) The National Archives lists which schedules are available by state and where to find them.

4) State archives and historical societies may also have copies, which may be digitized and online.

Related post: 6 Common Genealogy Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Final thoughts

Even though African American genealogy can be very challenging, documents like these lists are one tool for tracing families before the Civil War. Because so few other records exist that named slaves and where they were born, these are a valuable genealogical resource.